Prelude:

Sudden Violence

You know those stories your parents tell about when you were young and they caught you diving off the roof into the pool? Or maybe with a pack of matches underneath the bed and several charred black, a thin line of smoke curling upward? You always seemed to get caught at the precise moment of incrimination, your parents left to wonder just how they had managed to produce the living embodiment of Huck Finn. Amusing in retrospect, at the time these acts represented that special brand of madness permissible only in youth. Thankfully for all involved, the division between nature and nurture was sufficiently ambiguous even then. Chaos had an evergreen alibi. In spite of all this, there remained transgressions that went undiscovered. Such as two brothers at an anonymous apartment, time and place forgotten, inserting Mortal Kombat into a Sega Genesis. They might have been 7 and 5, or 6 and 4, but surely far too young to learn the mechanics of uppercutting someone’s head off their damn body. Such technicalities were far from relevant in the moment however, with no adults in the vicinity. Somehow the corruption proceeded uninterrupted and in secret.

Our run was forgettable, and though we couldn’t get a copy of Mortal Kombat at our house until years later, discovering that unapologetic, frantic button masher remains one of the most exhilarating memories of my early life.

TEST YOUR MIGHT!

Prelude (Continued):

Nineteen Ninety-Something

It’s the toughest jobs that need doing, and that extends even to obscure tasks like making the case for Mortal Kombat (with a god damn K!) as the greatest video game adaptation of all-time. My dubious qualifications and deep-seated bias aside, here I present you with the unassailable format of this essay:

Chapter 1: Revenge is the clearest lens

Chapter 2: $500 Sunglasses

Chapter 3: Shang Tsung’s 500 year plan

Epilogue: Brutality

While I purposefully meander throughout this treatise, you may be tempted to ask “are we there yet”? Consider what kind of a question that is for one who has always been there? All roads don’t merely lead there, all roads are there. This qualifier should be unnecessary, friends, but you are navigating fanatical territory here. I am as serious in my devotion to middling kung-fu fantasy as Sonya Blade is when blowing a thug through plate glass at a thrash concert. Just as no one stopped moshing then, I will not slow around these hairpins in the interest of coherence either. IT HAS BEGUN.

Chapter 1

Revenge is the clearest lens

Based solely on my enthusiasm for this film, you can probably already guess that Mortal Kombat is not the sort of movie that goes in for the cold open. The most important priority is dealt with first: drilling the audience with that original theme song. I mean, if you ever wondered what annihilating your inbox on cocaine would feel like, turn up and have at it! Irrational exuberance right out of the gate. Director Paul W.S Anderson (the “other” Paul Anderson) probably sledgehammered the ancient gong on the downbeat of 1 on The Immortals‘ legendary ‘Techno Syndrome’ with a P.A’s numb skull. That’s true in my head no matter what the internet says.

Not that it’s really the point or anything, but the basic story of the film is that warriors are chosen to defend earth in a tournament called Mortal Kombat. If they lose 10 straight times, a horde of extra-terrestrial invaders from Outworld will enslave humanity for a really long time, probably. The film deals with the 10th tournament, with the Outworlders having won the previous 9 in a row (because of course they had). This is serious business, so Ralph Macchio didn’t get so much as a tryout for this shit.

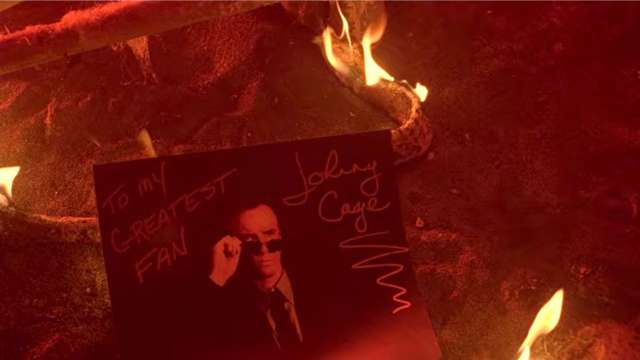

Liu Kang, descendent of Kung Lao, has a dream wherein his brother is killed by Sorcerer and unrepentant metalhead Shang Tsung. He visits his Grandfather at the temple of The Order of the Light to demand he represent them at the tournament. Liu, played by Robin Shou, seems like a competent martial artist, but there is some clear nepotism at work here also. More importantly however, he has unreal flow and wants revenge!

In short order, we meet Sonya Blade and Johnny Cage. Sonya is with the police and openly hunting her partner’s killer for revenge. Johnny is a Hollywood actor who laments not being taken seriously as a legit martial artist. They each are lured onto the least seaworthy barge imaginable bound for Shang Tsung’s island where the tournament is conveniently being hosted. The dock scene where they all board contains some of the best and worst comedy the film has to offer.

The best: Liu Kang grimly striding toward the ship and narrowly avoiding a face full of sparks from a random street welder…Yes, a welder, at night in the middle of the main artery of an international seaport. This moment is clearly either unscripted and Anderson just said “screw it, leave it in”. Or even better, it is scripted and just comes off like a moment of jittery humanity from our lead badass. Pure gold.

The worst: Shang Tsung’s creepy BDSM fantasies involving Sonya begin here. The guy is so obsessed he eventually blows his own plan by dawdling and dressing her up like she was heading to an audition for a live-action version of Heavy Metal.

Despite Raiden’s claim that revenge will be Liu Kang’s downfall, it is his most believable source of motivation. His hatred for Shang Tsung is what spurs him on throughout the film, more so than any feeling of responsibility to the Order or his companions. We easily identify with his desire to see Shang Tsung dead, whereas it is much harder to understand the complicated goals of the Order, Raiden, or even Kitana (why exactly does Tsung let her roam around helping Liu Kang??). Similarly, Sonya’s sole purpose for even entering the tournament is to kill Kano. She has this singular focus alone, and thereafter is abducted by Tsung to secure a fraudulent victory.

The idea explored in Mortal Kombat is that revenge is ultimately a pursuit that can be manipulated by evil forces to weaken and corrupt good people. Raiden attempts to suggest that there is another path, one that involves self-responsibility and overcoming self-doubt to achieve a sort of enlightenment. In theory, that way lies the mastery required to defeat Shang Tsung. In a crucial moment at the end of the film, Liu realizes that his brother Chan chose to fight Shang Tsung. Destiny functioning as a kind of salve for grief in this context…That aside, even if Liu had been there Chan still would have died.

While it might be the case that Liu’s initial obsession with revenge is unhealthy (his unmitigated rage leading him to issue early challenges to Shang Tsung that are mercifully ignored) it remains true that his desire for revenge is the fuel that feeds his competitive fire. He may not have a plan, he may not quite have the skill, he may be ignorant of the true shit he is wading through, but god damn it is he pissed! And somehow his rage is self-justifying, pure, and when set against the right soundtrack, utterly unimpeachable. When Tsung says to Johnny Cage that foolishness is the true sign of a hero, he should properly be speaking to Liu. The guy is undeniably winging it. Cage’s brand of revenge is more deliberate however.

Chapter 2:

$500 Sunglasses

Quite possibly the most pervasive truism about this film is that Johnny Cage is the best character. He has the best lines, purest motivation, and exudes a refreshing smugness at simply beating the shit out of lesser competition. While Liu Kang is the best fighter, Cage has a criminally underrated run through the tournament.

His first opponent is Scorpion, in what is the best fight sequence in the entire film. He gets dragged into hell and actually holds his own for the whole contest. Cage finishes him in a boneyard of his past victims.

Death by evisceration / decapitation.

He then dispatches past champion and animatronic monstrosity Prince Goro. Goro’s horrific top-knot and limited mobility aside, Cage takes out Tsung’s top lieutenant essentially 5 fights into the tournament. This effectively forces the Sorcerer into a series of errors that lead to his defeat by Liu Kang. For this reason, you could put Cage’s run up right up there against Liu Kang’s. Liu beats Sub-Zero and Shang Tsung in official combat (Kombat?), but technically also beats Reptile. This probably gives him the overall edge. Yet, it can still be argued that Johnny’s plan to challenge Goro early is the reason earth won the tournament ultimately. The only character with any coherent plan- albeit one formulated on the fly -Johnny Cage occupies dual status as the warrior with least reason to be there and yet the warrior without whom all would be lost.

Chapter 3:

Shang Tsung’s 500 year plan

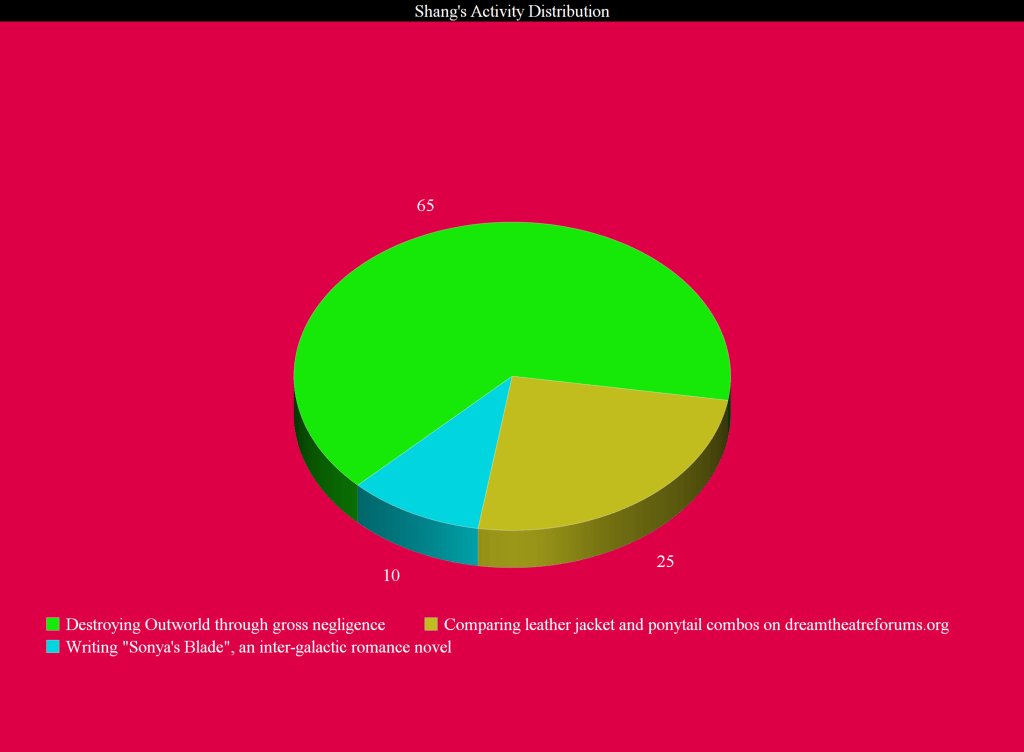

In the headhunt for a senior executive to fulfill the Emperor’s aggressive expansion mandate, somehow Tsung’s resume made it to the top of the heap. The only plausible explanation for this being that a premium must have been placed on arrogance and delusions of grandeur. Only these qualities could account for how Tsung believed merely showing up with a leather jacket and Goro would be enough to win the tournament against Kung Lao’s descendant, Johnny Cage, and a host of other decent warriors. He didn’t even enter Reptile into the tournament, which made no sense whatsoever. He allowed Kitana to actively work against him, and had no contingency whatsoever when Goro went down. One is left to wonder just how this guy spent his time?

Talk about organizational failure. Centuries of incompetence, totally unchecked, with seemingly zero accountability. Shang would have been ousted inside a week at Neutron Jack’s GE, let alone as leader of Shao Kahn’s Militia. It is highly doubtful that a 360 review of his appalling management style was at any point conducted, but to say the guy is no productivity maven might well be the most hysterical understatement possible.

Epilogue:

Brutality

The legacy of Mortal Kombat is more complicated than one would initially assume. It was a success by all accounts, having eclipsed its production budget by more than 600%. It was really the first live action video game adaptation to be considered a triumph. However, it is seldom pointed to as a point of origin for the modern video game adaptation, stylistically or otherwise. It is difficult to explain just why that is, especially since most adaptations prior to its release had been critical and commercial failures (Super Mario Brothers (1993) and Double Dragon (1994) being two prominent examples). Additionally, the film was made for the right audience, by the right director, at precisely the right cultural moment. The game had exploded in the arcade scene of the early 90s and was a strong seller on consoles thereafter (Genesis, SNES). Producer Larry Kasanoff purchased the rights to adapt the film around the same time. By 1995, many of the kids who had spent several years with the property were primed for the live action release. Paul Anderson implied in the behind the scenes companion documentary to the film that he made Mortal Kombat for those arcade gamers first and foremost. Well…you can certainly tell he enjoyed making the movie, even if it isn’t clear that it was aimed at the audience he cites in particular. It was properly rated PG-13 for “non-stop martial arts action and some violence” (MPAA), effectively drawing in players and mainstream teens alike.

The success of the film was not merely down to good luck and timing however. Mortal Kombat boasted some of the best martial artists, stunt coordinators and performers available at the time. Robin Shou was a legitimate Chinese action film star, having nearly 40 films to his credit leading up to his high-profile American film debut. Shou was so competent as a martial arts performer that he helped design the choreography for many of the film’s key fight scenes, including the classic between Scorpion and Johnny Cage.

Mortal Kombat should have shot Robin Shou to the moon. Here was a handsome, athletic, Asian male lead with legitimate chops as a martial artist and without the traditional language barrier many face when trying to transition to western cinema. His debut American film premiered a full two years before Jackie Chan would take the world by storm in Mr.Nice Guy (1997). Curiously though, Shou’s career never really took off. His film credits after Mortal Kombat are as sparse as they are varied. Appearances in Beverly Hills Ninja (1997) and the sequel to Mortal Kombat immediately followed, but then a full five year period passed with no credits. It remains a mystery precisely why that is, but a Reddit AMA with the actor in 2015 suggested that the issue was partially related to typecasting. As in, Robin Shou didn’t fit the traditional preconception of the Asian male film star. He stands six feet tall, doesn’t possess an accent, and looks more imposing than Jackie Chan or Jet Li. Perhaps he was deemed less suitable for the brand of action comedy that Chan perfected in the late 90s and early 2000s? His work in Beverly Hills Ninja suggests otherwise, but perception has a way of manipulating reality in its wake.

Further complicating Mortal Kombat’s legacy is just how slowly the world moved after the film’s success. In terms of large scale, high profile, live action video game adaptations released in the ensuing decade, Tomb Raider (2001) and Resident Evil (2002) were the next obvious touchstones. A full six years on, these films featured none of the humor or unbridled lunacy that so characterized Mortal Kombat. Tomb Raider was self serious in tone and offered little beyond familiar action adventure set pieces. Resident Evil, Anderson’s next foray into the world of video game adaptations, featured aspects of classic thrillers and some creative body-horror. It would be the next great live action video game adaptation, and further demonstrated Anderson’s ability to not only understand the source material but also the audiences he was making these films for.

The upcoming reboot of the Mortal Kombat franchise for this generation of fans appears to be leaning into world-building and CGI primarily. The early signs are that it will not feature the humor of the original. At least not intentionally, that is. James Wan is the creative force behind it, and it’s hard to know if that’s a good fit given his varied filmography. Oddly enough, the remake both has big shoes to fill and a rather blank canvas to work with. MK fans of the day are extremely unlikely to have played anything other than the recent games (Mortal Kombat X and Mortal Kombat 11). These share little with those from the early 90s visually, but they do still feature Ed Boon as creative director and retain the gleeful, comic gore that made the series so much fun. So in that regard perhaps there is reason to be optimistic.

Mortal Kombat may have been the beneficiary of ideal timing, but the filmmakers knew exactly what the film was, who it was for, and what made it fun. Given all we know now about how these adaptations can go wrong- and look no further than the veritable graveyard of horrendous films adapted from beloved franchises for proof of that -perhaps Mortal Kombat’s legacy is that it remains the blueprint for how not to screw this up. For a film of such modest aspirations to begin with, that sounds just about right to me.